What is enlightenment, really? Is it something we must attain, something to discover, or something already present, here and now? And what happens once you “get enlightened”? What is the experience of enlightenment like?

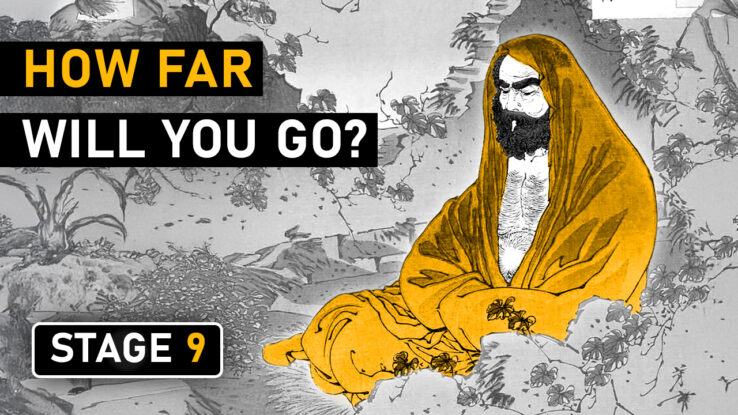

There is a famous Zen teaching that offers profound answers to these questions. This teaching is not a scripture or some philosophical treatise, but a series of images. The “10 Oxherding Pictures”, these are called, or the “10 Bulls”, and they depict the Zen path in 10 stages of progressive awakening.

2 Views on Enlightenment

There are two major views on enlightenment in wisdom traditions. One view sees enlightenment as the culmination of a long journey of cultivating the body-mind. Through practice and discipline, we break down our conditioned patterns of behaviour and attune the mind to the subtler dimensions of experience. Through consistent effort, we turn the intellect and the organism into instruments of perceiving ultimate reality. Early Buddhism is a classic example of this view, and you can learn more about it in my video on the Noble Eightfold Path.

The other view sees enlightenment as an absolute reality that is always and everywhere the case. Seeking enlightenment is as absurd as searching for space or waiting for time. Yes, we are usually unconscious of our enlightened nature, so we must learn to recognize it. But turning this recognition into some sort of goal or practice is a fundamental mistake, which further separates us from the truth of our being. Jiddu Krishnamurti offers the clearest teachings on this I know of and, again, I have a video on Krishnamurti’s teachings you can watch.

So, which view of enlightenment is more accurate? More importantly, which one would better help you perceive your true nature, here and now?

Enter Zen Buddhism and the 10 Oxherding Pictures.

Zen Buddhism’s View on Enlightenment

Zen fully embraces the paradox of enlightenment. On the one hand, it says, we are always already enlightened; on the other hand, it takes great effort and dedication to realize our enlightenment. On the one hand, Zen depicts awakening as the most dramatic, transformative experience; on the other, it is the most ordinary fact of life.

Instead of trying to untangle such paradoxes intellectually, Zen navigates them through the use of stories and images. The great psychologist Carl Jung also spoke of the power of symbolic, figurative language to reconcile those deeper aspects of life which seem paradoxical to rational thinking.

In any case, let me present to you Zen’s answer to the paradox of enlightenment. The 10 Oxherding Pictures, with their accompanying verses and commentary. These images present the path of enlightenment, beginning with the state of ignorance and confusion, and ending with what Jung calls individuation and what Nietzsche calls becoming oneself. Enlightenment.

Zen’s Map of Awakening

Exploring the 10 Oxherding Pictures can give us a map to orient ourselves on our own path of awakening. No two paths are identical, but there are universal patterns of experience, and it is helpful to be able to recognize them. The 10-step sequence we have here has guided generations of meditators, so it is a tried and tested map of awakening. Still, bear in mind your actual path will never be so linear. It will often skip over some stages, then backtrack, then disappear completely, only to reappear when you least expect it. If anything, this makes having a map even more useful.

So, let’s dive into Zen’s 10 Oxherding Pictures and let’s see what they have to teach us about the path and essence of enlightenment…

Before we continue, I want to thank everyone who supports my work! These pieces are the fruits of my personal journey, and each one takes me over a month of work. If you’re finding value here, you can support my work by joining our community on Patreon. This will also give you access to exclusive content, community events, and the ability to submit your questions for guests on my podcast. Thank you for your support!

The 10 Oxherding Pictures

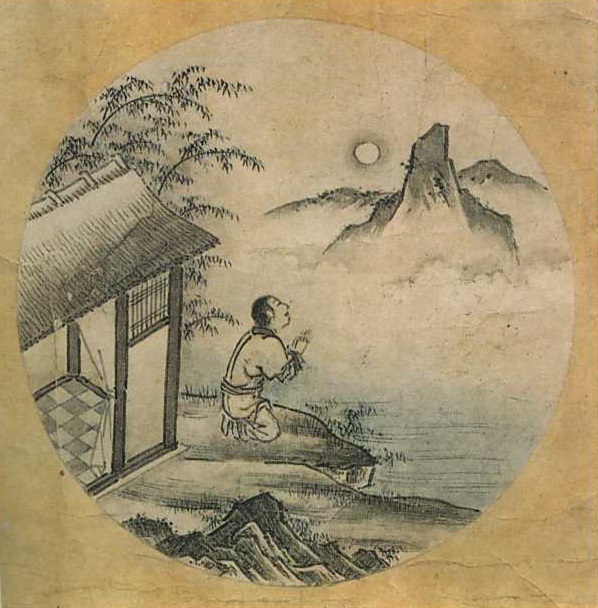

1. The Search

In the pasture of the world, / I endlessly push aside the tall / grasses in search of the Ox. / Following unnamed rivers, / lost upon the interpenetrating / paths of distant mountains, / My strength failing and my vitality exhausted, I cannot find the Ox.

The path of awakening begins with a sense of confusion, exhaustion, and anxiety. We may liken this to insight into the Buddha’s First Noble Truth, which is that life, as ordinarily lived, is full of dissatisfaction and disappointment. Our strength is failing, and we can no longer keep up the endless pursuit of fulfillment that never comes.

We also find ourselves in a “thicket of views”, as the Buddha put it. Our mind is full of conflicting ideas and opinions, what Bob Dylan calls “useless and pointless knowledge”. Today’s culture of mass-distraction makes this even more true than it was 9 centuries ago, when Zen master Kakuan wrote his Oxherding verses.

The Great Doubt

But this beginning stage of enlightenment is more than simply the state of confusion. It is the state of realizing you are confused. The insight that you are lost, that you are not aligned with your true nature, that you are seeking happiness and meaning in the wrong places… This is an insight.

In Zen, this stage is called “the Great Doubt”, and it represents the first stirrings of disenchantment with the ways of the world. This disenchantment is vital, as Carl Jung points out, as it shakes us awake from unconscious participation in the life of the herd.

This stage corresponds to the early Buddhist notion of saṃvega, which Thanissaro Bhikkhu defines as:

The oppressive sense of shock, dismay, and alienation that come with realizing the futility and meaninglessness of life as it’s normally lived; a chastening sense of our own complacency and foolishness in having let ourselves live so blindly; and an anxious sense of urgency in trying to find a way out of the meaningless cycle.

Thanissaro Bhikkhu, Affirming the Truths of the Heart

As the first stage of the awakening journey, saṃvega, or the Great Doubt, is a common experience. Today, we may call it “depression”, “burnout”, or an “existential crisis”, and we will try to get rid of it as quickly as possible. Zen, however, depicts this stage as an important initiation. Many of us never develop the Great Doubt, but remain submerged in the collective, mistaking conformity and slavery for status and achievement.

2. The Footprints

Along the riverbank under the trees, / I discover footprints. / Even under the fragrant grass, / I see his prints. / Deep in remote mountains they are found. / These traces can no more be hidden / than one’s nose, looking heavenward.

The second stage of awakening corresponds to the Buddha’s Third Noble Truth. It is the insight that, although life is full of dissatisfaction, satisfaction is possible. Although the world is rife with ignorance, wisdom is attainable.

This might seem like a slight improvement over the first stage, but in fact, it is a revolution. Should we get stuck in the Great Doubt, we end up as cynics or nihilists. We become alienated critics of the world, unable to participate in life, mocking the very notions of meaning or the sacred.

Discovering the footprints, however, shows us that amidst life’s confusion, there is a narrow path to follow. We may discover pointers to that path in wisdom texts, works of art, or in the teachings of living masters. Pointers may also come from nature, from meaningful coincidences, and from our dreams. The unconscious, Jung has shown, naturally nudges us into the direction of psychological growth.

At this stage, we have an intimation of what direction to follow, but we are still confused. To proceed, we need to explore and experiment. The way forward requires initiative and dedication. As Christ says:

Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and the door will be opened to you.

Matthew 7:7

3. Perceiving the Ox

I hear the song of the nightingale. / The sun is warm, the wind is mild, / willows are green along the shore – / Here no Ox can hide! / What artist can draw that massive head, / those majestic horns?

Our search finally yields true spiritual bounty. Our senses are open, and the ox can no longer hide. As the commentary goes:

As soon as the six senses merge, the gate is entered. Wherever one enters one sees the head of the bull! This unity is like salt in water, like color in dyestuff. The slightest thing is not apart from self.

Senzaki Nyogen, Paul Reps, Zen Flesh, Zen Bones

Our true nature, we find, is indistinguishable from sensory experience, like the saltiness of salt water. At the same time, our true nature is wholly other than experience, transcendent, something no artist can draw, and no words can describe.

Here is our first glimpse of ultimate reality, what Zen calls kenshō. It is a revolutionary discovery that opens new vistas of freedom, peace, and insight. The excitement of this makes it easy to get stuck at this stage, thinking you’ve done all the work, seen all there is to see. Our Zen map tells us, however, we haven’t even walked the path halfway.

Entering the Stream of Enlightenment

In early Buddhism, there is a similar concept, called “stream entry”. Once we perceive the conditioned nature of experience and the unconditioned dimension of nirvana, we have entered the stream of awakening. Scripture says we are then guaranteed to realize nirvana within 7 lifetimes. But what is the difference between one who has entered the stream and a fully liberated arahant? Venerable Narada gives us the following simile in the Pali Canon:

It’s as if there were a well along a road in a desert, with neither rope nor water bucket. A man would come along overcome by heat… and thirsty. He would look into the well and would have knowledge of ‘water,’ but he would not dwell touching it with his body.

Kosambi Sutta; SN 12.68

So, we shouldn’t settle for just seeing the water. We must find a way to get to it.

Moving past this third stage is no longer a matter of experimenting and seeking. We have found the ox. We now need to capture it. Whether we use the metaphor of catching an ox or of drawing water from a well, one thing is certain: we need a rope.

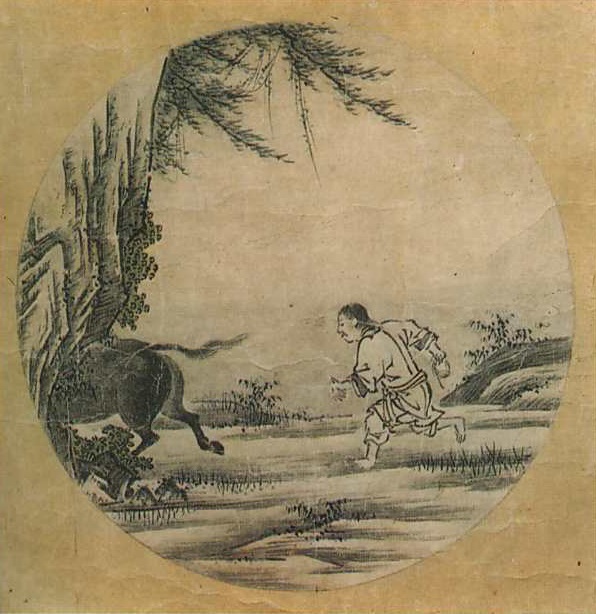

4. Catching the Ox

I seize him with a terrific struggle. / His great will and power / are inexhaustible. / He charges to the high plateau / far above the cloud-mists, / Or in an impenetrable ravine he stands.

Here comes the great struggle. Some traditions see the notion of spiritual struggle as backwards. Jiddu Krishnamurti, for one, shows how spiritual effort is a fundamentally dualistic, ego-fueled notion. The act of striving, of self-discipline, builds up the very sense of self one is supposed to become free of.

Zen is infamous for its strict approach to meditation. But note that from all 10 stages of the path, only here does struggle play a role. As we’ll see, the road of enlightenment leads beyond effort to a state of complete harmony. In stage 4, however, we strain in body, mind, and spirit. What was a brief peak experience at stage 3 must now become our everyday reality.

Spiritual Practice

Buddhism views the mind as originally pure, radiant, and awakened. Awakening, then, is not something to acquire, but something to uncover within oneself. The act of uncovering it consists of, essentially, paying attention. Paying attention to all the movements of the body-mind until the body-mind becomes transparent and reveals our “original face”, as Zen calls it. Our face before our parents were born… Before the world came into being.

You can think of spiritual effort like training wheels. When learning to ride a bike, we must adopt a whole new paradigm for movement, and this takes time. Using training wheels allows us to learn the basics slowly, giving the body-mind time to adjust. The day comes when we take off our training wheels and never need them again, and this is precisely because they have served their purpose.

The same must be our relationship to spiritual effort. To form any clinging to practices or habits here risks depriving us of the joy of riding the bike of enlightenment freely, without depending on any support.

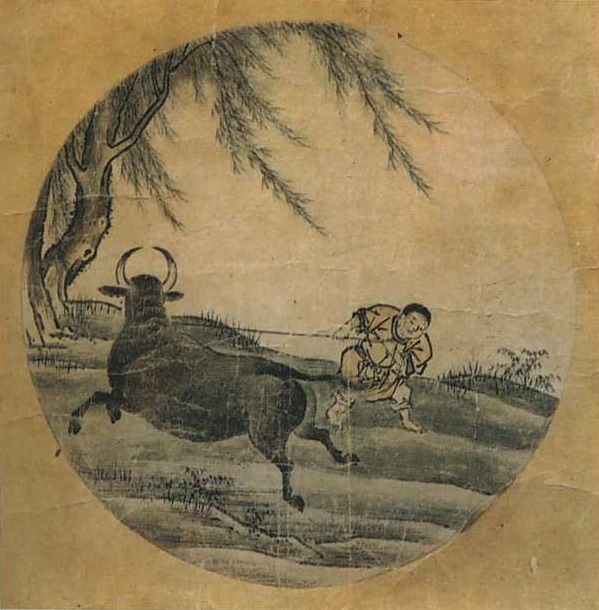

5. Taming the Ox

The whip and rope are necessary, / Else he might stray off down / some dusty road. / Being well-trained, he becomes / naturally gentle. / Then, unfettered, he obeys his master.

Midway on the path of enlightenment, our practice has settled; it has become effortless, free.

We still hold the whip and rope. Craving and ignorance are bound to show up now and again, and we must be ready. But the rope is loose, and the ox tame.

We have our back to the ox, too, no longer needing to keep a constant eye on him. We have begun to trust our naturally awakened state. The body-mind has grown restful, present, and compassionate.

Since this stage is such an improvement over our long period of struggle, it is easy to take it for the end of the path. We have successfully sought out and settled into awakening. We are in a constant relationship with our original face.

This is all well and good, but as long as there is a relationship, there is a distinction. As long as my true nature is something I experience, practice, or attain, then I am one and it another. The path forward reveals itself once we begin to surrender our ambitions of gaining and attaining. Once we put aside the rope and whip.

6. Riding the Ox Home

Mounting the Ox, slowly / I return homeward. / The voice of my flute intones / through the evening. / Measuring with hand-beats / the pulsating harmony, / I direct the endless rhythm. / Whoever hears this melody / will join me.

Finally, the day comes when we take off our training wheels and hop on the ox. “I return homeward”, says Kakuan’s poem. We are done now with seeking, catching, and taming. Even effortless practice is now too effortful for us. We no longer even lead the ox. We know he will take us where we need to be, when we need to be there.

Ox and ox-herder are now in perfect alignment. This results in spontaneous, creative expressions of awakening and a newfound sense of joy and freedom. Here we may become teachers to others. There is no distinction now between practice and play. We begin to become like little children.

Note here, it is easy to interpret the end of practice too literally. Seen from the outside, our practice may continue as usual. Within us, however, a great shift has occurred. We no longer sit to meditate with a certain technique or goal in mind. If we sit, it is no longer practice, but our way of being in the world, like eating, sleeping, or going to the toilet.

At this advanced stage, our spiritual and our everyday life are in perfect alignment… But alignment still means two separate things. Riding the ox, no matter how freely, is still a subtle form of domination and attachment. We have gained all there is to gain, and now we know gains are fetters too. Freedom, as long as it is dependent on anything, is no freedom at all.

7. The Ox Transcended

Astride the Ox, I reach home. / I am serene. The Ox too can rest. / The dawn has come. In blissful repose, / Within my thatched dwelling / I have abandoned the whip and ropes.

Finally, we are home; the time of wandering is over. The rope we once used to catch the ox now unravels into stillness. The ox, also, is no longer our property, but set free. Letting go of all attempts to acquire, we bask in the dawn of liberation.

We once learned that effort is an impediment to enlightenment. Now we learn that enlightenment, too, as an idea, is an impediment. We let go of all attempts to understand, imagine, or name our true nature. The mind stops producing images of the unconditioned, knowing all images are false idols.

Emptying the Mind

Inner and outer, conditioned and unconditioned, awakened and ignorant… these, we see, have been false dichotomies from the start. The conflict between them has ever only been a conflict of concepts, and concepts cannot touch the reality of what is, here and now. This insight finally uproots all desire and ends our search. We find ourselves at home, always and everywhere.

We are done now with the path… But the path is not done with us. Without meaning to, in our surrender, we have broken the final fetters on the mind. And as Meister Eckhart writes:

God must pour himself according to the whole of his capacity into all those who have abandoned themselves to the very ground of their being, and he must do so so completely that he can hold nothing back of all his life, all his being and nature, even of his divinity, which he must pour … into those who have abandoned themselves for God and have taken up the lowest position.

Meister Eckhar, Sermon 7

Here, at the lowest position, the body-mind finally becomes completely transparent. The world, too, becomes transparent , and our original face finally gazes on itself.

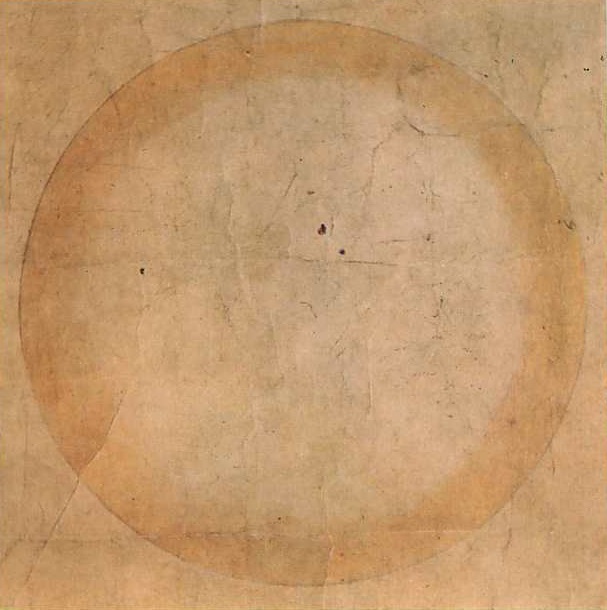

8. Both Self and Ox Transcended

Whip, rope, person, and Ox – / all merge in No Thing. / This heaven is so vast, / no message can stain it. / How may a snowflake exist / in a raging fire. / Here are the footprints of / the Ancestors.

I can give no better commentary on this stage than what Arvo Pärt says about it with his music:

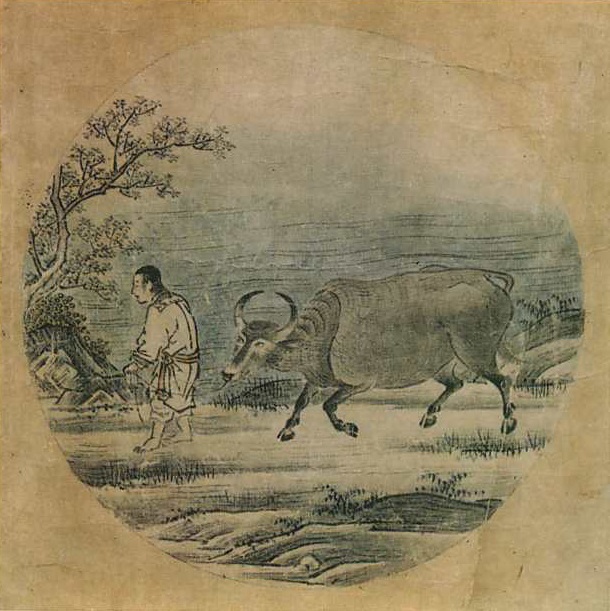

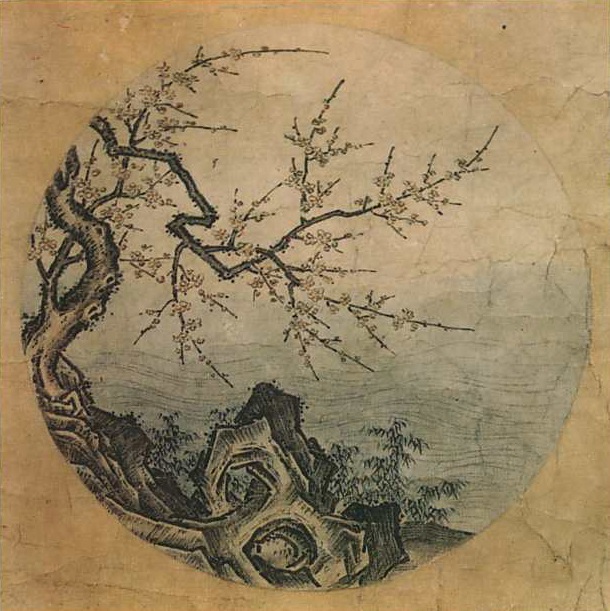

9. Reaching the Source

Too many steps have been taken / returning to the root and the source. / Better to have been blind and deaf / from the beginning! / Dwelling in one’s true abode, / unconcerned with and without – / The river flows tranquilly on / and the flowers are red.

One would think that insight into the ground of all being is the end of the Zen path. Indeed, early versions of the Oxherding pictures ended with the realization of emptiness (or shunyata). I have an in-depth video on what emptiness means in Buddhism, and you can watch that to learn more.

Kakuan, however, in his wisdom, knew better than to depict emptiness as the completion of the path. The greatest Buddhist philosopher, Nagarjuna, once warned that those who cling to form can be healed through insight into emptiness, but those who cling to emptiness are beyond all help. Similarly, the Zen master Joshu was once asked, “When a man comes to you with nothing, what would you say to him?”. Joshu answered: “I would tell him to cast it away!”

So, Kakuan added two stages of awakening that follow the insight into emptiness. These final stages close the arc of enlightenment and show that the path is not about retreating from the world. Quite the contrary.

Beyond Emptiness

Here, then, in the 9th stage of awakening, we are back where we started. We are no longer home, as we were in the 7th stage, but out in the wild again. We have gone into that ultimate “homelessness” of which the Buddha spoke; we are no longer taking shelter in a sense of self. We no longer belong to this or that, nor does anything belong to us.

Where we once thought there was a self, our self, now we find the whole world. If we look at the 9th Oxherding picture, we see no person represented. There is only the spontaneous unfolding of nature, the flowing of the river, the redness of the flower, and the miraculous awareness of it all.

But for all this emptiness and homelessness, we are, as the poem tells us, “dwelling in [our] true abode”. That is to say, freedom. A freedom not gained or produced. A freedom we recognize has always been here, from the very moment we set out on the path.

Returning to Awakening

Seeing this may make us wonder why we’ve spent so much time and effort just to return where we started. But this is more than simply a return. As Eliot writes:

We shall not cease from exploration / And the end of all our exploring / Will be to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.

T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets

This, then, is what follows after the veil of form is lifted and we perceive the emptiness underneath it all. The veil falls again, but this time we know it has never been a veil. Form, we once discovered, is emptiness… but now we know also that emptiness is form. The absolute, we now know, is absolute; it is never not present in its entirety.

Our past mystical pursuits now seem completely misguided. The mystery of the infinite is always available, even in the most trivial, ordinary things. The quiet wonder of a river flowing is richer than any theory, doctrine, or concept. This insight, perhaps, is what drove Zen master Tokusan to burn all his scrolls of philosophy after his awakening.

Finally, we know there is no need to do anything, go anywhere, or become anyone to reach the source of reality. The source is, always has been, and always will be here and now.

10. Return to Society

Barefooted and naked of breast, / I mingle with the people of the world. / My clothes are ragged and dust-laden, / and I am ever blissful. / I use no magic to extend my life; / Now, before me, the dead trees / become alive.

The final fruit of enlightenment is us. A simple human life, free of all pretense, all striving, all repression, compulsion, and anxiety. A simple human life, fully present to the wonder of existence. This, Zen says, is the completion of the path.

Christ once reprimanded his followers with these words:

… unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.

Matthew 18:3

This sums up the Zen path. The final destination of the path is the kingdom of heaven, and by the time we return there, we have attained what is most difficult; we have become like little children. Simple.

Enlightened Simplicity

It is difficult to explain or describe simplicity, as any such attempt breeds complexity. The intellect can be sharp or dull, slow or fast, wide or narrow, but it can never be simple. Simplicity is the harmony of one’s whole being, and it is not something we achieve through effort. It is the gift we arrive with as children, and the dream we pursue all our adult lives.

The Zen tradition is full of stories that give a taste of this simplicity. For example, one day a monk approached Joshu. The monk asked: “Master, I read in a sutra that all things return to the One, but where does this One return to?”

If somebody were to ask me that, I’d give them a lecture on interdependent co-arising; in fact, I have an hour-long video on that. But what was Joshu’s answer?

The master replied: “When I was in the province of Tsing I had a robe made which weighed seven chin”.

When is a non-answer the right answer?

Converted into a Buddha

Concerning the final stage of the path, Chögyam Trungpa writes:

[Here] is the fully awakened state of being in the world. Its action is like the moon reflecting in a hundred bowls of water. The moon has not desire to reflect, but that is its nature.

Chögyam Trungpa, Mudra

When we “become like little children”, we are no longer teaching anything, and yet everyone around us grows wiser. One may say it is life that now teaches through us, but this is too contrived a description. A fully enlightened being transcends all categories of thinking, being too simple for comprehension.

The fully-enlightened sage, the commentary says,

is found in company with wine-bibbers and butchers, he and they are all converted into Buddhas.

As translated by D. T. Suzuki

When Dostoevsky wrote that “the soul is healed by being with children”, it is this he meant. I urge you to spend some time with a child, without checking the clock for a while, without thinking of your next task. This will give you a taste of what it is like to be converted into a Buddha.

The final fruit of enlightenment is us. We are born again as the most extraordinary miracle on earth: a simple human being. A child.

To learn more about Zen practice and philosophy, I invite you to my podcast with Zen master Henry Shukman. There, we discuss the paradoxes of awakening, the pitfalls of meditation, and the use of koans as guides to enlightenment.

Thank you for reading, and remember: What you seek is seeking you.

See you next time,

Simeon